Fortune – Bringing the Fire: A Q&A with Bioinspirationalist Jeff Karp

Fortune – Bringing the Fire: A Q&A with Bioinspirationalist Jeff Karp

Source: Fortune

Jeff Karp, a leading biomedical engineer, discusses where, why, and how academic-business ventures can be most successful.

The biomedical industry is driven by scientific innovation. Yet, as anyone who has worked in R&D can tell you, harnessing the kind of creativity necessary for innovation is easier said than done. But there’s a new methodology in play that is making fascinating strides in the development of new medical technologies. And it’s a process that often starts not in the lab but at the zoo.

Welcome to the world of bioinspiration, or an emerging scientific discipline where scientists and designers look to the natural world to solve industrial and medical challenges. One can see bioinspirational approaches in nearly every industry. Velcro was based on the way burrs attach to clothing. Aerospace engineers once looked to birds in flight to better design jet wings. Materials scientists used the properties of the mammalian capillary system to help design better microfluidic systems. But, today, biomedical engineers are hoping that the biological world can help them tackle complex medical problems – and that bioinspirational techniques can help them create safe, sophisticated technologies that can help patients heal faster and more efficiently.

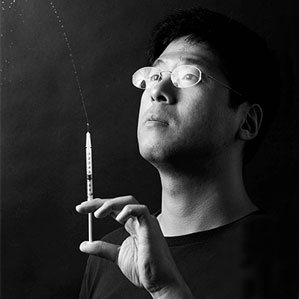

Jeff Karp, director of the Laboratory for Accelerated Medical Innovation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, is fast becoming the face of bioinspiration. Karp’s laboratory has used bioinspirational methods to create surgical staples modeled after porcupine quills, skin graft adhesives based on parasitic worms, and cancer detectors that work like jellyfish tentacles. But Karp also has a business resume. He has founded two bio-inspired companies, Gecko Biomedical, a company that specializes in medical adhesives, and Skintifique, a skin care manufacturer. This modern day academic entrepreneur talks with Fortune about the power of bioinspiration, why he founded his own companies, and whether bioinspiration is just a flash in the pan.

Q: So just what is bioinspiration, exactly? And how is it transforming the biomedical industry?

Karp: Bioinspiration has actually been around for a long time. It’s basically taking a basic idea in nature and improving upon it for your own purposes. Every living thing – every plant, every animal, every creature that exists today – is here because it has solved an incredible number of challenges and evolved to tell the tale. Mother Nature has managed to solve quite a few problems over the years. And so we can use bioinspiration to help us come up with new ideas to tackle tough problems.

Solving medical problems is extremely challenging. In healthcare, there’s a lot of pressure to drive down costs, to make things efficient, and, of course, to make things safe. It’s tough to find new ideas to bring to the table. So bioinspiration, returning to nature for those new ideas, is a great way to reframe and reconsider those problems and come up with creative, innovative, and plausible solutions.

For example, something as simple as a surgical staple. Right now, the kind of staples that are used in surgeries can sometimes leak and lead to complications and infections. So to come up with ideas to make them better, we looked to porcupines. Their barbs were a great source of inspiration. They are barbed in such a way that they go pretty easily but are really hard to pull out. So we created a synthetic system, based on that barb, that mimics the reduced penetration force and the increased pull-out force and is fully degradable. And we’re hoping that this kind of design in a surgical staple results in less leakage and reduced bacterial infections.

Q: But how do you find the solutions in nature to get your inspiration from? Field trips to the zoo?

These ideas come from all over. Certainly, we’ve had people go to the zoo, or the aquarium, or just spend a lot of time researching different examples in nature on the web. But it comes down to the problem or challenge you are trying to solve. You have to ask yourself, “Is there some species in the world that does this well? If so, how are they doing it?” Then you go back to the lab and figure out how you can do it.

Q: You do such fascinating research. Why found your own companies?

Karp: There are generally three different ways to translate an invention to a product. You can give a company a direct license. You can do sponsored research for a company, which could lead to a license later. Or you can start your own company. But in any of these cases, we ask ourselves several questions before moving forward.

If we are licensing the technology, is there a champion in the company who is going to be the lead on advancing the translation? Make sure it gets through all the hurdles? And then, in that case, what is the role for the researcher? The academic’s role needs to be clear. Sometimes, once the company starts advancing the technology, they keep the researchers at arm’s length. The company may not keep you informed, you may not even know what the challenges are or if you could offer something to address them. So if the project flounders, it’s more likely to die.

When you have a great idea that not only solves an important medical challenge but is also something that will translate, you want to see it end up in the clinic. And, in my experience, when you start your own company, you can increase the potential for success.

Q: A recent report based on university-business collaborations in the United Kingdom suggests that academics lack the cultural and commercial know-how to successfully transfer technology to the marketplace. Given that you work on several university-business collaborations, what’s your take on that?

Karp: Succeeding in academia and in industry does require completely different skill sets — and the cultures are also quite different. However, there can be a lot of synergy if both sides understand each other. And that synergy is not trivial. It has a high activation energy.

Academia is a great place to generate new ideas, to quickly test new proofs of concept, and to move inventions to relevant pre-clinical models. But once we get to a certain point, it’s hard to move an invention along. Academia’s just not a great place to do commercial scale-up, in general terms, especially for life science-based projects. There are more reasons than not why a company is likely to fail. So the most important thing is for an academic to align with an exceptional entrepreneur when they want to move forward. But it’s not always an easy partnership.

So, I think having a good technology transfer center plus entrepreneurial facilitators can all help. I think if you look at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, for example, there’s a huge effort to bridge the gaps. Their Innovation Hub runs hackathons, innovation seminar series, and pitch contests. They also schedule academic/industry events to cultivate relationships. Also, I think academic institutions that actively recruit successful innovators with deep ties to industry can serve as an inspiration to others and show both academics and business people what is possible and how to get it done.

Q: So with those cultural differences, what does an academic bring to the board room?

Karp: More than anything, they bring the fire. They have the passion, the commitment, and the know-how. They are going to fight for their inventions. And they are going to nurture it as if it is their baby as you go through all the rigorous steps of bringing that invention to market.

Q: How do you determine who will be a good commercial partner in bringing your inventions to market?

Karp: As I said, I think starting your own company increases your chance of success. But you can’t do it alone. It’s extremely challenging. So you need to build the right team. You need to partner with someone who has started companies previously, who have raised money, who has gone through rough times and overcome those challenges, and who know exactly who to go to figure out the regulatory aspects, the scale-up, the best technology platforms to pursue, the large scale manufacturing, and the intellectual property concerns. Basically, you want to partner with someone who has been there/done that and can help you navigate every aspect of it.

Q: What should entrepreneurs consider when selecting academic partners in order to increase the likelihood of success?

Karp: I already talked about the fire. But beyond that, an entrepreneur wants to partner with an academic who understands the many challenges that lie ahead, and the commitment required to advance, solve the problem, and bring that technology to the clinic. The big things are finding academics who are flexible, fully committed to the success of the translational effort, and ready anytime to provide feedback and advice. Someone who understands that commercial translation is a very different world than academia. Some who will trust the entrepreneur and their team yet, at the same time, hold them to a high bar. Academics really drive the first five to ten percent of any translational project. But after they’ve created the prototypes, demonstrated the proof of concept, the entrepreneurs are going to lead the rest of the way. And the academics need to let them.

Q: Given that bioinspired medical technologies require this precarious balance of academia and business, where do you see this discipline going in the future?

Karp: I think we’re only at the tip of the iceberg. Bioinspiration is going to help us come up with a lot of new ideas in the biomedical industry – and in lots of other industries, too. That said, bioinspiration isn’t always easy. It requires a highly iterative process and a multi-disciplinary team. So successfully leveraging this kind of toolkit requires a strong commitment, a lot of flexibility, and a lot of collaboration – both when you are working in the laboratory and then trying to translate a technology for the clinic. It’s the only way it works.